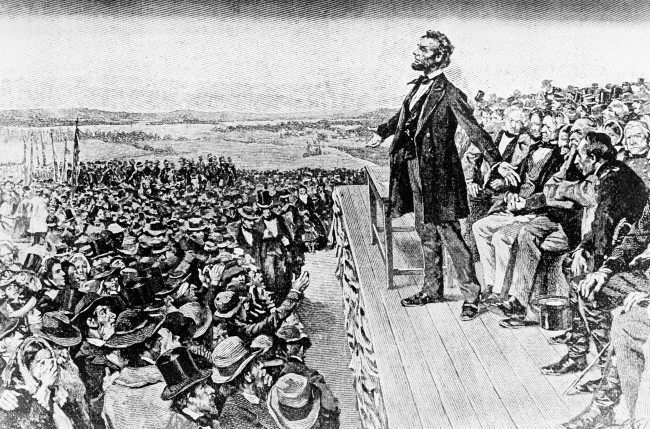

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered on the 19th of November 1863 remains one of the most impactful speeches of all time.

Perhaps the most impressive use of so few words the world has ever seen.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Brevity

Abraham Lincoln was the master of brevity. I hear people complain that they cannot possibly deliver a meaningful speech if they are only given 20 minutes to speak. The Gettysburg Address lasted only two minutes, contained 10 sentences and a mere 272 words. Rarely has so much power been delivered so succinctly.

Lincoln was not the keynote speaker of the day. He was only meant to offer a few words of support to the main event – one Edward Everett. A skilled orator who held the attention of the crowd for a whopping two hours. But it is Lincoln’s address that lives on, perhaps in no small part due to its economy of language.

Poetic Language

Even by 1863 standards, ‘four score and seven’ was a rather flowery way of saying 87. But this and other poetic flourishes create a sense of beauty and envelops the patriotic message. Interestingly, this method of referencing dates has been echoed by American Presidents over the years – no doubt, to evoke the spirit of the Gettysburg Address.

These days we favour short sentences designed to convey meaning with clarity. But along the way, we have lost some of the power of language. I think what I love most about the Gettysburg address is the loftiness of the language. It serves the message and somehow speaks to the higher ideals of the audience. It is a mistake, to dumb down your message to the point where you communicate dumbness.

Repetition

Simple repetition is one of the most powerful rhetorical devices we can all apply. Firstly, with anaphora, meaning the repetition of words at the beginning of succeeding clauses: “…we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground.”

Then Lincoln employs epistrophe, meaning the repetition of a word or phrase and the end of succeeding clauses: “…and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth”.

The Gettysburg Address

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

A Speech a Week Series

Words have the power to change the world. Speeches are used by leaders, revolutionaries and evangelists to persuade people to think differently, to feel something new and to behave in remarkable ways.

In this series, we will examine one notable speech per week. We hope to cast a wide net – including politicians, business leaders, preachers, entertainers and philosophers. These articles will consider matters of content and style to uncover the secrets of oratorical success.

By examing the components of speechcraft we can improve our own powers of persuasion. We will come to appreciate the craft of eloquence – guarding against silver-tongued miscreants whilst gradually building our own expressive capability.

If you would like to contribute to the series by suggesting a speech, please send us a message via the mojologic website.