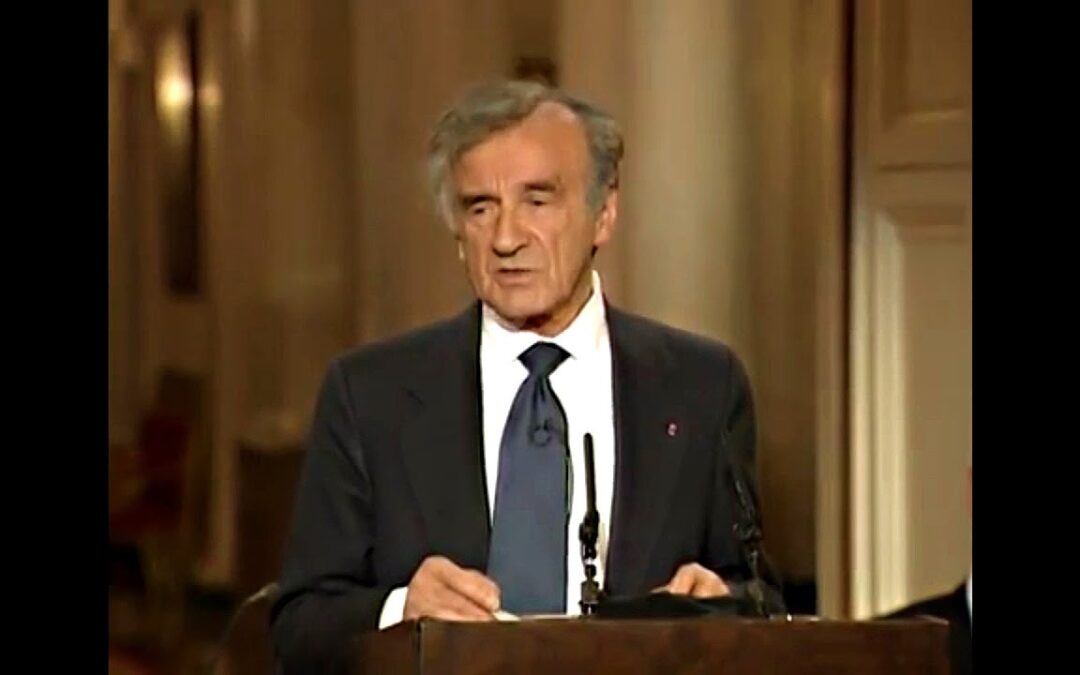

Elie Wiesel delivered a breathtaking speech at the White House on the 12th of April 1999. His message combined his own experience of the holocaust and the evil of apathy.

“The opposite of love is not hatred, it’s indifference… Even hatred at times may elicit a response. You fight it. You denounce it. You disarm it. Indifference elicits no response. Indifference is not a response. Indifference is not a beginning, it is an end. “

At the turn of the millennium, then US president, Bill Clinton and the First Lady, Hillary Clinton invited several intellectuals to speak at the White House. The speech delivered by humanitarian, author and Nobel Prize winner, Elie Weisel lives on in history.

The Importance of Timing

Like many masters of rhetoric, Wiesel successfully seized the moment. He linked the occasion of the new millennium, the location of the White House (hallowed ground of western democracy), the ceremony of the event (note Bill and Hillary Clinton seated behind the podium) with his message. So powerful a message as this – a plea for humanity. A call for people to recognise the seductive power of indifference and rail against apathy – this is an idea he rightly recognised as worthy of this particular stage on this particular day.

Personal Connection

Elie Wiesel’s speech begins with a personal story. We are instantly drawn into the narrative and we understand that Wiesel speaks from personal experience. No matter how committed the audience might be to reparation, no matter how abhorrent we find the actions of the Nazis during the holocaust, we cannot help but wince anew when presented with this story of personal experience.

Another reason why this speech is particularly powerful is a strong sense of ethos. According to Aristotle, ethos is the means of persuasion that relies on the character of the speaker and the audience’s ability to trust them. Even if you are not aware of Wiesel’s academic work and his literary achievements you would feel a sense of trust. This man has first-hand experience, a wealth of knowledge and the skill of eloquence with which to make a significant impact on anyone who listens.

“Fifty-four years ago to the day, a young Jewish boy from a small town in the Carpathian Mountains woke up, not far from Goethe’s beloved Weimar, in a place of eternal infamy called Buchenwald. He was finally free, but there was no joy in his heart. He thought there never would be again. Liberated a day earlier by American soldiers, he remembers their rage at what they saw. And even if he lives to be a very old man, he will always be grateful to them for that rage, and also for their compassion. Though he did not understand their language, their eyes told him what he needed to know — that they, too, would remember, and bear witness.”

Coherence & Bravery

The central theme of this speech is Wiesel’s claim that indifference is more dangerous than hatred. He sees indifference as a sin. He takes us back to the camps and brings us into the belief, shared with his fellow prisoners, that if only people knew what was happening they would intervene. But then the tragic, slow realisation; “And now we knew, we learned, we discovered that the Pentagon knew, the State Department knew.” A sick feeling of regret is rightly elicited. We feel complicit in this global indifference – that is exactly the point.

This speech is powerful because of the coherence of the speaker with the message. Every phrase is packed with meaning and delivered with passion. By this point, Wiesel must have told his story many times over, but we see and hear heartfelt emotion with every word. His gestures punctuate the despair he felt at Buchenwald. His expressions highlight his obvious conviction.

Exceptional bravery is displayed when Wiesel points out the indifference of the United States to the horrific acts of the Nazis. It is quite shocking to hear these words, so plainly spoken, in the setting of the White House with the sitting President watching on. If you watch the video, look out for Bill Clinton’s expression and demeanour when Elie Wiesel says:

“Franklin Delano Roosevelt died on April the 12th, 1945. So he is very much present to me and to us. No doubt, he was a great leader. He mobilized the American people and the world, going into battle, bringing hundreds and thousands of valiant and brave soldiers in America to fight fascism, to fight dictatorship, to fight Hitler. And so many of the young people fell in battle. And, nevertheless, his image in Jewish history — I must say it — his image in Jewish history is flawed.

The depressing tale of the St. Louis is a case in point. Sixty years ago, its human cargo — nearly 1,000 Jews — was turned back to Nazi Germany. And that happened after the Kristallnacht, after the first state-sponsored pogrom, with hundreds of Jewish shops destroyed, synagogues burned, thousands of people put in concentration camps. And that ship, which was already in the shores of the United States, was sent back. I don’t understand. Roosevelt was a good man, with a heart. He understood those who needed help.

Why didn’t he allow these refugees to disembark? A thousand people — in America, the great country, the greatest democracy, the most generous of all new nations in modern history. What happened? I don’t understand. Why the indifference, on the highest level, to the suffering of the victims?”

With this statement, Wiesel bravely adheres to the thesis of his own speech. He shows us what it means to make a stand. To reject indifference and apathy and to point out decisions and actions that do not measure up. He does not do this lightly. In fact, he shares the pain he feels in recounting these sad facts. But the facts matter. No matter how painful, we must hear them. Platitudes would only play into the evil power of indifference.

Powerful Conclusion

Elie Wiesel displays his rhetorical skill again in the powerful conclusion to this speech. Here he connects the central theme back to where we started – the young Jewish boy from the Carpathian Mountains…

“What about the children? Oh, we see them on television, we read about them in the papers, and we do so with a broken heart. Their fate is always the most tragic, inevitably. When adults wage war, children perish. We see their faces, their eyes. Do we hear their pleas? Do we feel their pain, their agony? Every minute one of them dies of disease, violence, famine.

Some of them — so many of them — could be saved.

And so, once again, I think of the young Jewish boy from the Carpathian Mountains. He has accompanied the old man I have become throughout these years of quest and struggle. And together we walk towards the new millennium, carried by profound fear and extraordinary hope.”