A Message of Warning to Men of Science

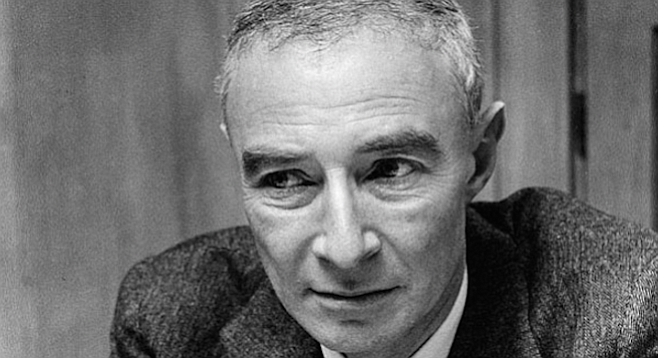

J. Robert Oppenheimer addressed the Association of Los Alamos Scientists on November 2nd, 1945.

In 1939 Franklin Roosevelt created the Manhattan Project – an Anglo-American project for the research and development of nuclear weapons.

In early August 1945 the US detonated two nuclear weapons over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Later that year, the leader of the Los Alamos team that developed the nuclear weapons, nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer delivered a speech to his fellow scientists warning of the ‘terrifying, powerful, incredible, awe-inspiring’ thing they had created. He clearly hoped his message would reach beyond the scientific community to provoke concern and right action for English and American policymakers.

The Role of the Scientists

75 years later our governments and citizens are once again looking to the scientific community for input, guidance and solutions. This time, the issue is climate change. It is a complex issue that many laypeople are trying to understand. There are many variables, interdependencies and theories.

Politicians are called upon, rightly so, to wade into the discussion. They want simple explanations and straightforward solutions. But if there is one thing scientists despise most it is an oversimplification.

Oppenheimer’s speech is a fine example of how words can reach across the divides of technical knowledge, tribalism and even geopolitics.

A Message of Warning

Oppenheimer spoke out in the months and years following WWII. His presence beyond the laboratory was somewhat unusual for a scientist. Oppenheimer contended that, we (mankind) must act carefully and morally when making decisions about the future place that nuclear weapons will occupy in our world.

He directly addresses his community in an appeal to principle. We (scientists) engage in our craft to improve the human experience. Secrecy and destruction are anathema to the principles of science. To perform our role we must be open, share information and embrace curiosity.

It is not possible to be a scientist unless you believe that it is good to learn.

Throughout this address, Oppenheimer makes an appeal to ethos. Anchoring the shared beliefs of scientists at the beginning and linking to this ‘compass’ throughout.

Lesson 1: Start Small and Build

Oppenheimer’s message is strong but he delivers it softly. Both in voice and words, he hints at the gravity of his appeal but lulls the audience in by signalling a gentle discussion.

This is achieved through the extensive use of guarding terms and qualifiers:

“I do not have anything very radical to say…”

“I don’t have anything to say that will be of immense encouragement.”

“I don’t know very much about politics”

“What has happened to us — is really rather major.”

Then he transitions to somewhat more emphatic language. By this point he has primed his audience to receive what might overwise be considered a confrontational message.

Lesson 2: Concede Premises, Opinions & Counter Arguments where Possible

If you have a contentious proposition then a useful technique is to lay out some of the counter-arguments you are likely to encounter. You can then refute these arguments to make your proposition more robust.

Oppenheimer puts forward a rather powerful argument about the very existence and value of science in society, but first, he offers a concession to any who might reject his analogy:

“But the real impact of the creation of the atomic bomb and atomic weapons — to understand that one has to look further back, look, I think, to the times when physical science was growing in the days of the renaissance, and when the threat that science offered was felt so deeply throughout the Christian world. The analogy is, of course, not perfect. You may even wish to think of the days in the last century when the theories of evolution seemed a threat to the values by which men lived. The analogy is not perfect because there is nothing in atomic weapons — there is certainly nothing that we have done here or in the physics or chemistry that immediately preceded our work here…”

Then follows his contention:

“…the very existence of science is threatened, and its value is threatened. This is the point that I would like to speak a little about.”

Which may have been rejected without laying some groundwork.

Oppenheimer concedes a number of potential counter-arguments, to make the point, that whilst these views may be correct and yet they do not detract from his central claim:

“…there was finally, and I think rightly, the feeling that there was probably no place in the world where the development of atomic weapons would have a better chance of leading to a reasonable solution, and a smaller chance of leading to disaster, than within the United States.“

“There has been a lot of talk about the evil of secrecy, of concealment, of control, of security. Some of that talk has been on a rather low plane, limited really to saying that it is difficult or inconvenient to work in a world where you are not free to do what you want. I think that the talk has been justified…”

“There are many people who try to wiggle out of this. They say the real importance of atomic energy does not lie in the weapons that have been made; the real importance lies in all the great benefits which atomic energy, which the various radiations, will bring to mankind. There may be some truth in this.”

“There are things which we hold very dear, and I think rightly hold very dear; I would say that the word democracy perhaps stood for some of them as well as any other word.”

Lesson 3: Connect the Audience to What They Stand For

This speech invokes an ethical argument – scientists and governments should do what is right. Such a bold declaration as this would be unlikely to resonate. It would sound preachy and be met with rejection. Instead, Oppenheimer connects his appeal to what the assembled audience collectively stand for:

“I think that we have no hope at all if we yield in our belief in the value of science, in the good that it can be to the world to know about reality, about nature, to attain a gradually greater and greater control of nature, to learn, to teach, to understand. I think that if we lose our faith in this we stop being scientists, we sell out our heritage, we lose what we have most of value for this time of crisis.”

Oppenheimer’s plea was a warning. Certainly, he had a direct and central warning to his audience – the collection of scientists at Los Alamos on that day in 1945.

His message was intended, also, to reach the ears of politicians. A warning against secrecy.

A Timeless Warning

Perhaps unwittingly, Oppenheimer also had a lesson for the scientists, politicians and polarised citizenry of today. His lesson emerges from the central tenets of scientific exploration.

The echoes of a speech delivered so many years ago elucidate a principle that could help guide us through our new and complex challenges that traverse the worlds of science and politics.

“But there is another thing: we are not only scientists; we are men, too. We cannot forget our dependence on our fellow men. I mean not only our material dependence, without which no science would be possible, and without which we could not work; I mean also our deep moral dependence, in that the value of science must lie in the world of men, that all our roots lie there. These are the strongest bonds in the world, stronger than those even that bind us to one another, these are the deepest bonds — that bind us to our fellow men.”

J. Robert Oppenheimer

Read the full transcript of Oppenheimer’s address to the Association of Los Alamos Scientists (2 Nov 1945) here.

__________________________________________________

A Speech a Week Series

Words have the power to change the world. Speeches are used by leaders, revolutionaries and evangelists to persuade people to think differently, to feel something new and to behave in remarkable ways.

In this series we will examine one notable speech per week. We hope to cast a wide net – including politicians, business leaders, preachers, entertainers and philosophers. These articles will consider matters of content and style to uncover the secrets of oratorical success.

By examing the components of speechcraft we can improve our own powers of persuasion. We will come to appreciate the craft of eloquence – guarding against silver-tongued miscreants whilst gradually building our own expressive capability.

If you would like to contribute to the series by suggesting a speech, please send us a message via the mojologic website.